The History of Hiroshima Sake

The History of Hiroshima Sake

The Progress of Hiroshima Sake ~Development of the Soft Water Brewing Method by Miura Senzaburo~

Hiroshima Sake is blessed due to an abundance of sake rice grown on fertile farmland, a mild climate, and a favorable environment.

When speaking about Hiroshima Sake, one must not forget to mention Miura Senzaburo, born in Mitsu, Akitsu Town, in 1897. Senzaburo made the most of ‘soft water,’ which had been considered unsuitable for sake brewing, and developed the ‘soft water brewing method,’ which was completely original at the time. Through this method, he succeeded in producing unique, mellow Hiroshima Sake with a gentle taste and a robust, full flavor.

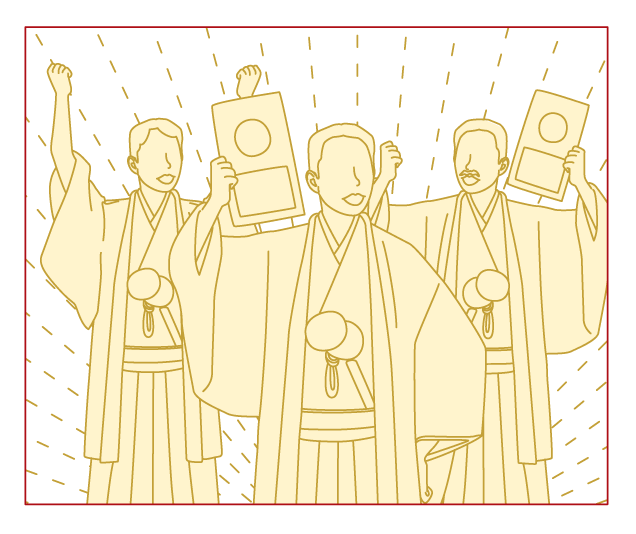

In addition, Hiroshima Sake won an overwhelming victory at the first All Japan Sake Competition held at the Institute of Brewing in Tokyo in 1907, instantly earning the prefecture recognition as a sake production area and bringing it into the limelight among sake-lovers throughout Japan.

Ever since, Hiroshima Sake has continued to make great strides and received great acclaimed.

Hiroshima Sake made rapid progress, and Hiroshima Prefecture––the location of Saijo (Higashihiroshima City, Hiroshima Prefecture)–became known as one of the three best sake brewing areas in Japan, alongside Nada (in Hyogo Prefecture) and Fushimi (in Kyoto Prefecture).

Click here to read the historical story of Hiroshima Sake.

Hiroshima Toji, Known for Their Traditional Hiroshima-style Techniques~Kiyoshi Hashizume’s Spirit of Training Successors is Passed Down~

Even after Hiroshima Sake came into the limelight, Miura Senzaburo continued to work hard, organizing a research society in his home area of Mitsu with the aim of improving techniques, and he put forth particular effort to train toji (chief brewers).

Kiyoshi Hashizume, who became the first head of the Brewing Department at the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Testing Laboratory (currently known as the Hiroshima Prefectural Food Technology Research Center), was influenced by Senzaburo and devoted himself to training Mitsu toji. He worked hard to provide and spread outstanding technical guidance, and contributed to training successors and establishing various toji guild associations. He devoted himself to improving the quality of sake brewed in Hiroshima Prefecture, and throughout his entire life, he never moved away from Hiroshima, where he served as a brewing technician for the prefecture, even going so far as to flat out refuse when ordered to transfer to another prefecture.

The spirit of these predecessors to improve techniques and train their successors is still being passed down to this day.

Hiroshima Prefecture held the first-ever Hiroshima Alcoholic Beverage Competition in June 1899, the first competition of its kind in the country, with the goal of improving brewing techniques and the quality of Hiroshima Sake. Although the competition was temporarily suspended for a number of years due to WWII, the 100th anniversary competition was held as a grand event in April 2005. (The name was changed to “Hiroshima Sake Competition” in 2006.)

The Hiroshima Prefecture Sake Brewers Association continues to hold the competition to this day, and Hiroshima toji continue to improve their techniques in order to improve the quality of their sake and to produce sake that matches the preferences of the consumers of the time.

In Hiroshima Prefecture, there are currently more than 40 breweries that produce their own unique variety of sake, all the while continuously striving to mutually improve each other. There are few other areas with such a large number of breweries. We invite you to seek out the brewery and type of sake that most pleases you.

Click here for introductions of each brewery

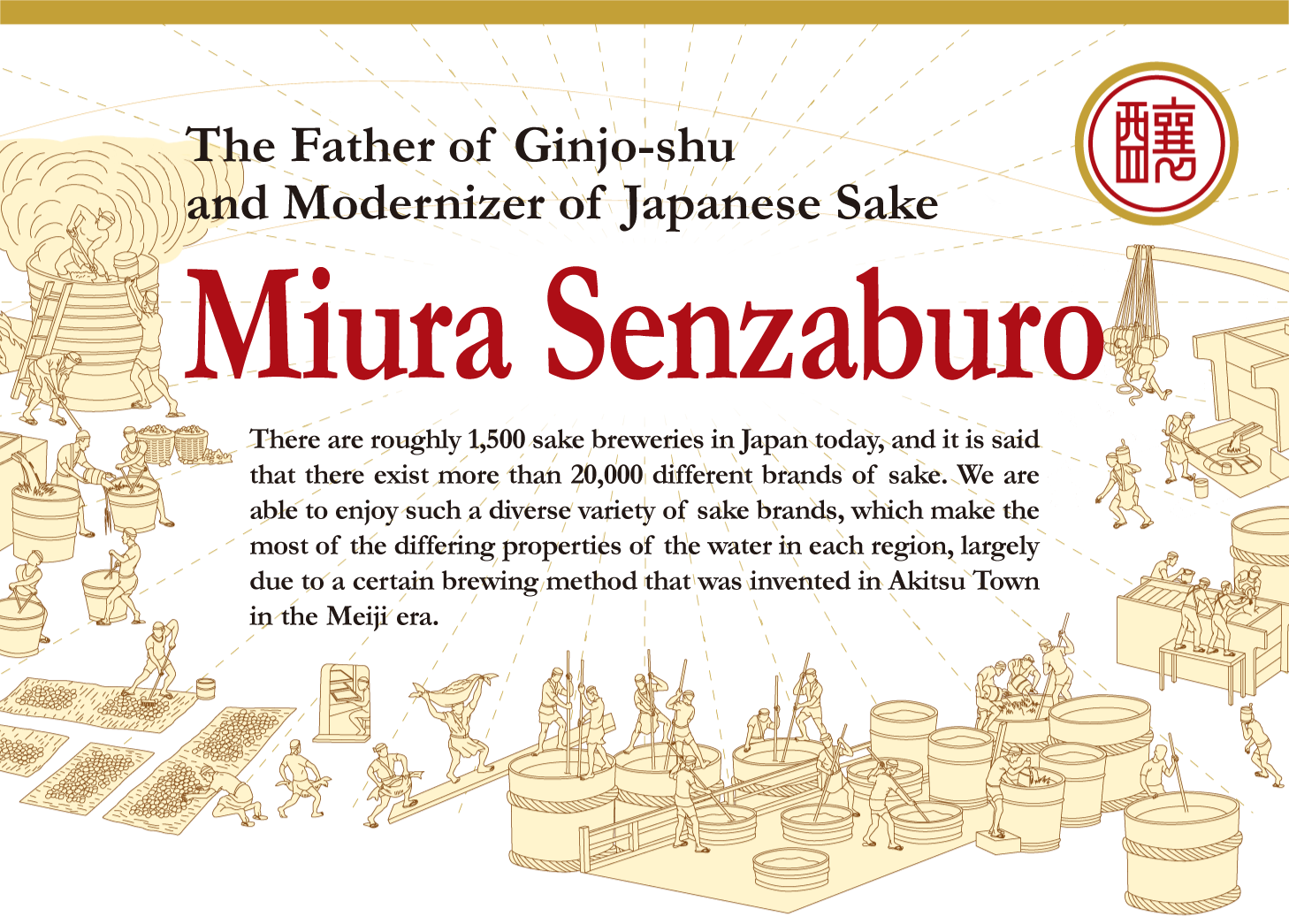

The Hiroshima Sake Story “Try One Hundred Times, Make One Thousand Improvements” ~Development of the Soft Water Brewing Method by Miura Senzaburo, the Father of Ginjo-shu~

1.What is Ginjo-shu?

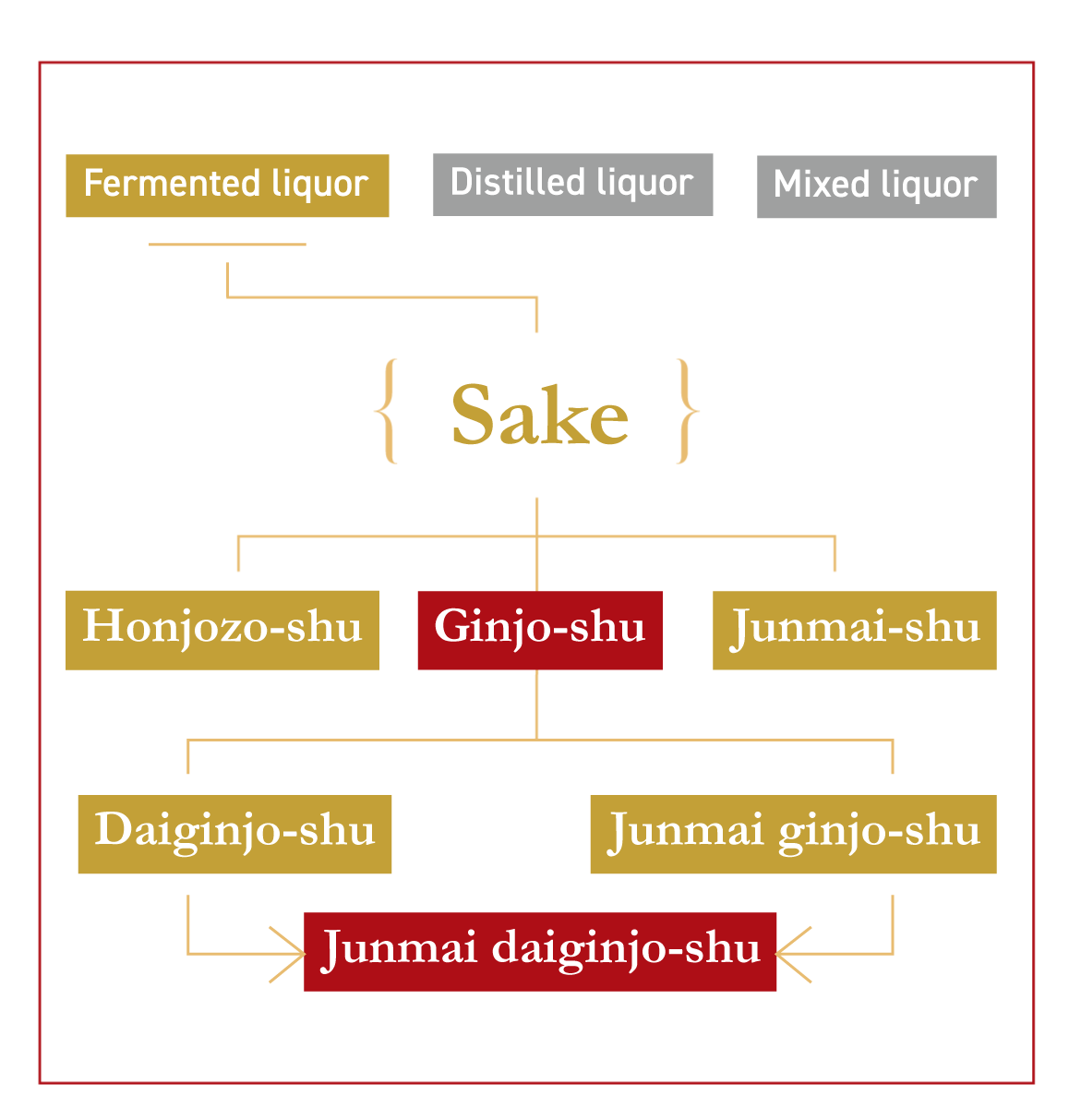

Alcoholic beverages are classified into three categories based on differences in their production method: Fermented liquor (wine, beer, sake, etc.), distilled liquor (shochu, whiskey, vodka, etc.), and mixed liquor (plum wine, vermouth, etc.). Japanese sake is a type of fermented liquor, and there are three specific class names that denote that the sake is of high-grade: Ginjo-shu, Junmai-shu, and honjozo-shu. Specific conditions relating to raw materials, production methods, and other factors have been established to determine whether or not a product may be labeled with these designations.

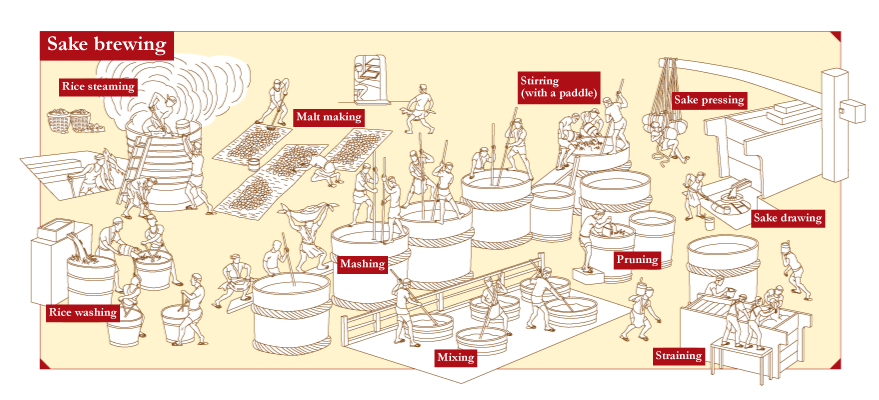

Ginjo-shu is characterized by its fruity, floral aroma (the ginjo aroma), and its delicate flavor is most striking when it is enjoyed cold or lukewarm. In terms of raw materials, it is made from rice, rice malt, and brewing alcohol. The rice used is grown specifically for brewing and is commonly called “proper sake rice.” The rice is shaved to at least 40% of its original weight (a rice polishing ratio of 60% or lower) and fermented at low temperature for a long period of time. If 50% or more of the rice is shaved, the sake will be labeled daiginjo-shu. If no brewing alcohol is used, it will be labeled junmai ginjo-shu, and if both of these conditions are met, the sake will be labeled junmai daiginjo-shu. The ginjo-zukuri method of making ginjo-shu became established as many toji (chief brewers) continued to improve their techniques throughout the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa eras. In particular, it was the Mitsu toji (in the area that is now Akitsucho, Higashihiroshima City, Hiroshima Prefecture), later known as Hiroshima toji, who are credited with establishing the origins of ginjo-zukuri and spreading it throughout the country.

2.The Sake Brewing Industry in Each Time Period

Sake brewing in Japan dates back to the late Jomon Period, when rice cultivation first began to propagate throughout the Japanese islands. In ancient times, sake was mainly brewed by Shinto shrine maidens and immigrants to Japan from the Asian mainland. In the Middle Ages, it was mainly carried out by priests and sake merchants. Up until the early Edo period, sake used to be brewed all year round. However, due to later advances in fermentation technology, kan-zukuri (cold brewing), carried out during wintertime, became the prevalent method. The scale of production continued to expand along with developments in equipment and facilities. After the autumn harvest, many farmers would also engage in sake brewing during the wintertime.

During the Edo period, rice was the center of the Japanese economy, and only a limited number of breweries had the right to produce and sell sake, which is made from rice. However, the situation changed drastically in the Meiji era. Regulations were eased, and landowners and merchants who possessed enough capital began to brew sake.

Mitsu Village in Akitsu was a collection point for the annual rice tax and the location of a storehouse established by the former Hiroshima Domain. The village prospered as a port town through which rice was transported to Osaka. Rice became a commodity following land-tax reforms, which stipulated that tax payments be made in cash instead of rice, and merchants in Mitsu began to take over the rice within the storehouse. Some of the merchants who gained access to large amounts of rice entered into the sake brewing business, and the number of breweries in Akitsu increased rapidly.

3.Akitsu Sake’s Boom and Bust

In the early Meiji era when much of the sake on the market was of inferior quality, Akitsu sake gained popularity. The area earned acclaim as a sake production center, and during this time, more and more people in the surrounding regions began to focus on sake brewing as well. However, the breweries in Akitsu were not able to maintain stable production because the mash would spoil during the brewing process or while in storage nearly every year. In addition, the Meiji government decided to levy higher taxes on sake (sake brewing accounted for the highest volume of national tax revenue in the late 1890s and early 1900s). Furthermore, due to advancements in transportation, high-quality sake from Nada and Osaka flowed into Hiroshima Prefecture, and breweries in Akitsu fell on hard times, with some even going out of business.

Miura Senzaburo, a sake brewer in Akitsu, was also one of these newcomers. He too naturally suffered from spoilage during brewing and storage. He attempted a variety of solutions, including building a new brewery, but nothing worked. He also went to Nada to work for a year as a brewer and learn sake brewing methods. During this time, he devoted himself to researching brewing methods, collecting books on brewing techniques and exchanging ideas with sake brewers and toji (chief brewers) in various regions.

4.Establishment of the Soft Water Brewing Method that Formed the Basis of Ginjo-zukuri

After returning home, Miura Senzaburo continued to investigate the cause of the repeated spoilage during brewing and storage. After many failures, he finally realized that it was due to the water quality. The water in Nada was hard and mineral-rich, which facilitated fermentation and produced good sake. However, when he examined the water quality in Akitsu, he found that it was all soft water with a low mineral content.

“I guess this is why brewers in Nada went to the trouble of transporting miyamizu, special water from wells in Nishinomiya, to use in brewing. However, I can’t transport water all the way to Mitsu. That being the case, instead of imitating brewers in Nada, I will research how to produce a type of sake that is suitable for Mitsu.”

From that point onward, he began searching for an unconventional method that would enable him to stably produce good sake even when using soft water.

Miura Senzaburo’s motto was “try one hundred times, make one thousand improvements.” After a series of repeated research attempts in line with this motto, in 1897, he established his new method, which included nurturing the malt well, brewing at low temperature, using thermometers, etc. to monitor temperatures, keeping good records, and ensuring sanitation.

In the same year that he established his soft-water brewing method, Miura Senzaburo gathered together the toji (chief brewers) and other brewers in and around Akitsu to teach them his new brewing method. The following year, he also publicly released a book titled Kaijoho Jissenroku (“Practical Record of the Revised Brewing Method”), in which he described his techniques. Toji in Hiroshima Prefecture, which has an abundance of soft water, were greatly inspired to conduct their own research. Miura Senzaburo also established a guild association for Mitsu toji and put forth other efforts to train toji, who systematically learned the brewing method. Eventually, the soft water brewing method became widely established in Hiroshima and quality also improved.

5.Hiroshima’s Progress Excites Sake Brewers Across the Country

At the first All Japan Sake Competition held in 1907, brands of sake brewed in Hiroshima won the highest awards––the first and second prizes–– beating out sake brands from both Nada and Fushimi, and many other brands of Hiroshima Sake had good results, greatly surprising interested parties throughout the country. The realization that good sake could be made even with soft water is said to have inspired and encouraged sake breweries in soft water regions nationwide.

The Mitsu toji who mastered the revised brewing method actively engaged in sake brewing in various other parts of Japan, as well as in Hawaii and even Sakhalin. Through their efforts, the soft water brewing method spread throughout Japan and formed the basis for subsequent sake brewing research. Notably, Miura Senzaburo, who established the soft water brewing method, also became known as the “father of ginjo-shu” due to the great influence he had on ginjo-zukuri.

If sake brewed in Nada using miyamizu can be likened to “male sake,” giving the impression of a boy running around in the northern winds and growing up to be strong, then ginjo-zukuri can be likened to “female sake,” giving the impression of a delicate girl raised in a clean, warm environment with all measures taken to ensure that she does not catch a cold or get a stomachache. When you drink carefully brewed ginjo-shu, please recall the story of Hiroshima Sake.

Reference:Hiroshima Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore “Sake Culture in Hiroshima”

Akiko Ikeda, “The Man Who Created Ginjo-shu”

Reference and illustration reprinting:JA Zen-noh Minori-Minoru Project “AGRIFUTURE Vol.86”